Mar Vista

Tract

History

The Mar Vista Tract was designed by Gregory Ain

in collaboration with Joseph Johnson and Alfred Day. Ain was a significant

"second generation" modernist architect who had worked with and was

influenced by the first

generation of California Modern masters - European immigrants Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler.

Ain believed in bringing good design to the

masses. During his youth, he lived for a time on a cooperative farming colony,

founded by Job Harriman, a socialist his father had supported in the 1911 Los Angeles mayoral

race. Ain belonged to the school of thought that espoused architecture's

potential to shape a more egalitarian world. He is credited as being the first

architect to design a house that did not contemplate servants. A lot of Ain’s

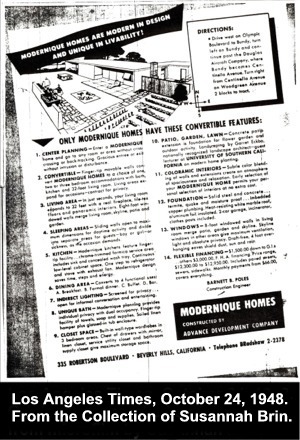

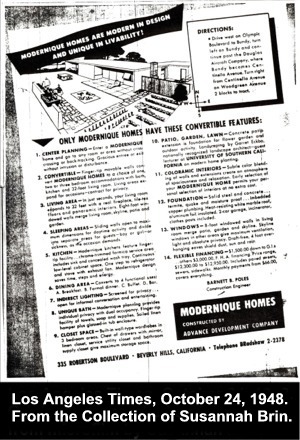

ideals were achieved in the "Modernique Homes" development, the name

under which the Mar Vista Tract was marketed in 1948. The intent of the Mar

Vista Tract was to create a housing development that provided cost efficient

housing while advancing the cause of Modern architectural design.

Ain believed in bringing good design to the

masses. During his youth, he lived for a time on a cooperative farming colony,

founded by Job Harriman, a socialist his father had supported in the 1911 Los Angeles mayoral

race. Ain belonged to the school of thought that espoused architecture's

potential to shape a more egalitarian world. He is credited as being the first

architect to design a house that did not contemplate servants. A lot of Ain’s

ideals were achieved in the "Modernique Homes" development, the name

under which the Mar Vista Tract was marketed in 1948. The intent of the Mar

Vista Tract was to create a housing development that provided cost efficient

housing while advancing the cause of Modern architectural design.

The Mar Vista Tract development was planned in

1947 for a hundred houses on a 60-acre site. The first stage was 52 houses,

which turned out to be the final stage. By rotating the one floor plan in different directions,

Ain was able to create a sense of variation between the houses. Garage placement in

relation to the house also gave each house its own individuality.

The average size of the houses was 1,060 square

feet, exclusive of the double garage. The sales price of the homes was about

$12,000, considerably higher than the contractor-inspired houses around nearby

Venice Blvd. that were then selling for about $5,000. The main selling points were the convertible features, the ultra-modern

design, and colors.

The average size of the houses was 1,060 square

feet, exclusive of the double garage. The sales price of the homes was about

$12,000, considerably higher than the contractor-inspired houses around nearby

Venice Blvd. that were then selling for about $5,000. The main selling points were the convertible features, the ultra-modern

design, and colors.

Through the use of a folding wooden panel separating the

living room from an additional space that was designed to be used as a master bedroom or extension to the living room, Ain achieved an adaptable space for any

size family. Similarly, a sliding panel divided a large single bedroom into two areas

in the rear of the house. The idea was that the resident could have one to three

bedrooms, depending on the needs of the family at any given time. The houses

were each painted in different color combinations, using the Plochere Color

system, an ink-mixing system developed in 1948 by one of Southern California’s

earliest color consultants. Subtle color blending of the interior space was

designed to create an “atmosphere of spaciousness and relaxation.”

Interestingly, the palette was much richer and more colorful than the white

sometimes associated with Modern design. Rather, it followed in the

footsteps of Le Corbusier's harmonic color concepts. The exteriors

were rich in color, and the interior of each house had a color scheme matching

its exterior color. All rooms used this color scheme, and each wall was a

different shade of the theme color.

Ain read some of Dr. Benjamin Spock’s writings

on parenting and incorporated what he learned in the design of the cabinetry

separating the kitchen, entry hall and living room, according to Anthony Denzer,

an architect who is writing his doctoral dissertation on Ain. Denzer explains

that since women at the time spent so much time in the kitchen, Ain felt the

area needed to be open so that the mother could keep an eye on the children

playing in the living room and out in the yard. When more privacy was

wanted a Venetian blind hidden in a recess above the table could be lowered as

could a panel under the table allowing the family to close off the kitchen from

the living room.

Ain read some of Dr. Benjamin Spock’s writings

on parenting and incorporated what he learned in the design of the cabinetry

separating the kitchen, entry hall and living room, according to Anthony Denzer,

an architect who is writing his doctoral dissertation on Ain. Denzer explains

that since women at the time spent so much time in the kitchen, Ain felt the

area needed to be open so that the mother could keep an eye on the children

playing in the living room and out in the yard. When more privacy was

wanted a Venetian blind hidden in a recess above the table could be lowered as

could a panel under the table allowing the family to close off the kitchen from

the living room.

In working with Garrett Eckbo in the design of

the community landscape, Ain found a kindred spirit. Eckbo was more

interested in the design of public landscaping and

creating unpretentious free flowing useable gardens for the common person than

with the creation of privately owned landscapes for the privileged. He played a

central role in the formulation and practice of Modern landscape architecture.

While studying landscape architecture at Harvard University, Eckbo was credited

with helping launch the “Harvard Revolution." This design thesis rejected

the predominate Beaux Arts style of landscape planning which emphasized

formality and strict division of the formal and informal garden, in favor of a

more casual and fluid use of space, utilizing clustered plant materials,

geometric abstraction, and circular space to lend compositional unity to the

landscape. In the Modernique Homes development, these concepts are evident.

Eckbo used a large number of planting materials

to create a park-like atmosphere along the streets. He opened up the space

between houses and created buffer gardens to allow for exterior spatial social

interactions. Except for the Model House, the backyards were basically left for

the homeowner to landscape. Although, shade trees were spaced along the rear

property lines. While the original plantings along the street have

often been replaced, the layout and many of the originally planted trees and

shrubs survive. Original plantings of Magnolia trees along the parkway along Meier St,

Melaleuca along the parkway of Moore Street and Ficus along the parkway of

Beethoven Street lend unity to the landscape. In 2003, the Mar Vista Tract

became the first Post-World War II Modern historic district in the City of Los

Angeles, officially known as an Historic Preservation Overlay Zone

("HPOZ"). - Hans Adamson

and Amanda Seward.

Further Reading:

The Architecture of Gregory Ain by David

Gebhard, Harriette Von Breton and Lauren Weiss, Hennessey + Ingalls, Santa

Monica, 1997.

Garrett Eckbo: Modern Landscapes for

Living by Marc Treib and Dorothée Imbert, University of California Press,

Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1997.

Gregory Ain Vista Tract Historic Resources

Survey prepared by Myra L. Frank & Associates for Los Angeles Planning

Department, Los Angeles, September, 2002.

The Second Generation by Esther McCoy,

Peregrine Smith Books, Salt Lake City, 1984.

Ain believed in bringing good design to the

masses. During his youth, he lived for a time on a cooperative farming colony,

founded by Job Harriman, a socialist his father had supported in the 1911 Los Angeles mayoral

race. Ain belonged to the school of thought that espoused architecture's

potential to shape a more egalitarian world. He is credited as being the first

architect to design a house that did not contemplate servants. A lot of Ain’s

ideals were achieved in the "Modernique Homes" development, the name

under which the Mar Vista Tract was marketed in 1948. The intent of the Mar

Vista Tract was to create a housing development that provided cost efficient

housing while advancing the cause of Modern architectural design.

Ain believed in bringing good design to the

masses. During his youth, he lived for a time on a cooperative farming colony,

founded by Job Harriman, a socialist his father had supported in the 1911 Los Angeles mayoral

race. Ain belonged to the school of thought that espoused architecture's

potential to shape a more egalitarian world. He is credited as being the first

architect to design a house that did not contemplate servants. A lot of Ain’s

ideals were achieved in the "Modernique Homes" development, the name

under which the Mar Vista Tract was marketed in 1948. The intent of the Mar

Vista Tract was to create a housing development that provided cost efficient

housing while advancing the cause of Modern architectural design.